By Silvia M. Diego, MD

Full Scope Family Physician, Principal Officer, Family First Medical Care, Modesto, CA

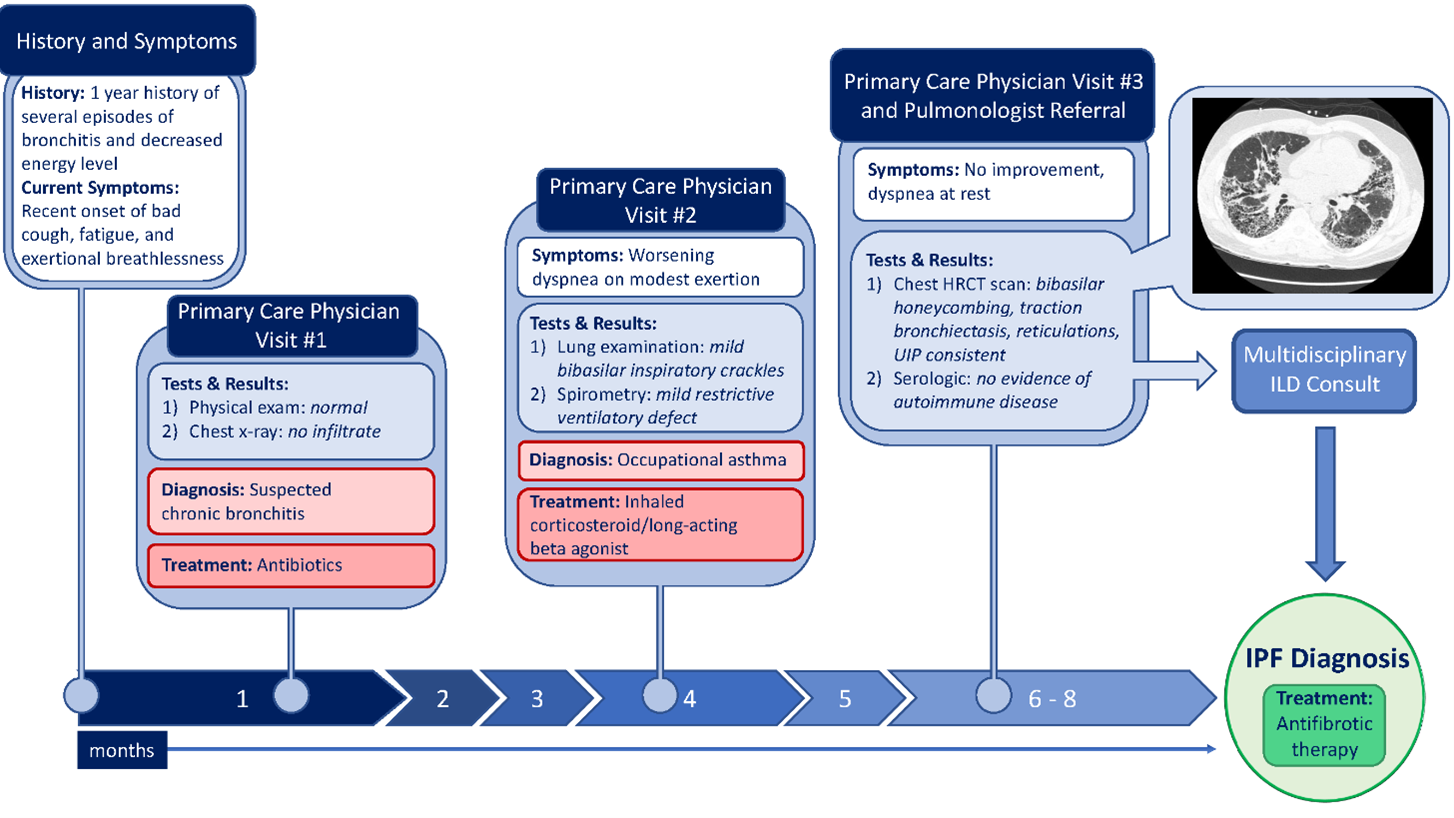

My 58-year-old patient, I’ll call him John for this article, came to me complaining of a bad cough, fatigue, and exertional breathlessness that started about 10 days prior. He describes several episodes of “bronchitis” and decreased energy level over the last year such that he is finding it much more difficult to continue his farm working job. He works outdoors in the fields during the week and at an exotic pet shop on the weekends.

He has a 20 pack-year smoking history but quit five years ago. He denies chest pain or palpitations and attributes his symptoms to being out of shape. Physical examination showed normal vital signs, and lung sounds were unremarkable. Chest X-ray showed no infiltrate. He was started on antibiotics for suspected chronic bronchitis.

Following the course of antibiotics, he began to feel better. Three months later however, the patient returned with worsening dyspnea on even modest exertion. He could no longer keep his full-time job. Lung examination revealed mild bibasilar inspiratory crackles. Office spirometry was suggestive of a mild restrictive ventilatory defect. Due to his exposure to exotic animals, he was prescribed an inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting beta agonist for presumed occupational asthma.

After eight weeks on the inhaler regimen, the patient noticed no improvement and felt more dyspneic, even at rest. In the office, he was noted to have hypoxemia and was referred to a pulmonologist. The pulmonary consultant recommended chest HRCT scan, which revealed basilar honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, and reticulations, all consistent with a usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern. Serologic studies showed no evidence of an autoimmune disease or a hypersensitivity reaction.

John was referred out and ultimately diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). He was started on antifibrotic therapy. See the patient map illustration her

IPF is a disease that often presents at the PCP level and early diagnosis is key to improving outcomes. A delay in diagnosis of IPF may lead to ineffective management.5

In this case study, there are several clues for the diagnosis of IPF. At the PCP level, there should be a high index of suspicion for IPF in patients with gradual progression of dyspnea, cough, and dry inspiratory basilar (Velcro®) crackles.6,7 A PCP’s awareness of common risk factors can help us identify IPF. Risk factors for IPF include age greater than 50, history of smoking, and male gender. 6,8

A definitive diagnosis of IPF is obtained with HRCT or lung biopsy identifying the common pattern of Usual Interstitial Pneumonitis (UIP) and other causes of UIP pattern have been excluded. 9 In this case, the HRCT is consistent with IPF and serologic data excludes autoimmune causes and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. It is very important to identify other possible etiologies to decrease exposure to possible causes such as mold, pets or toxins and commence treatment of autoimmune diseases or hypersensitivity pneumonitis if this has been diagnosed.

As mentioned previously, IPF can be mistaken for other common diseases. Initial CXR may remain normal for some time. Once I mentioned this case to a colleague, I heard they had a very unfortunate experience with IPF. One of their patients with known Cardiomyopathy for years was treated for CHF exacerbation several times through the course of 3 years. The patient was ultimately hospitalized with severe pneumonia and unable to be weaned off oxygen. He had a HRCT that showed the classic UIP consistent with IPF. A delayed diagnosis with poor prognosis and significant comorbidities led to his death. Awareness gives us PCPs an opportunity to be more vigilant in those cases that present as common pulmonary disease that appear to not improve.

There is no cure for IPF currently. As PCPs, we need to be able to educate our patients with IPF of any available therapy. Best prognosis and improved quality of life is seen in those patients treated in a specialized center for IPF. Most importantly we need to help improve our patient’s quality of life and continue to offer medical care and support with respect and compassion.

For more information:

American Thoracic Society:

General Information about Pulmonary Fibrosis (thoracic.org)

Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation:

What is Pulmonary Fibrosis | Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation

References

1. Meltzer EB and Noble PW. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:8.

2. Nalysnyk L et al. Eur Respir Rev. 2012;21: 126, 355-361.

3. Nathan SD et al. CHEST. 2011;140(1):221-229.

4. Zibrak JD et al. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14054.

5. Lamas DJ et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184(7):842-7.

6. Raghu G et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(6):788-824.

7. Raghu G et al. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25(3):409-419.

8. Olson AL et al. Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27(150):180077.

9. Raghu G et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(5):e44-e68.